It is well known that careful qualitative research can help inform survey design, especially when the issues are complex or new. An important challenge in agricultural policy is to find ways of improving yields and profits while also delivering environmental benefits. Natural resource management (NRM) packages which are designed to deliver on these twin goals have consequently become a policy priority. The jury is still out, however, on whether there is evidence to support the idea that farmers have successfully adopted climate-resilient practices when combined in such packages.

One of the challenges in assessing the evidence is measurement. NRM packages have multiple components and include a complex set of practices making it difficult to design survey questions that accurately measure adoption rates. To address the challenge, we conducted a qualitative study of a package of agronomic practices in Vietnam called “1Must Do, 5 Reductions” (1M5R), to design a good survey module to integrate in the forthcoming VLHSS (Vietnam Household Living Standards Survey). Under 1M5R the one “must do” is to use certified seeds, and the five prescribed reductions are on seed rates, pesticide use, fertilizer inputs, water use, and postharvest losses. The motivation here is that we felt that simply asking farmers if they adopted 1M5R would result in noisy (very possibly biased) data without telling us anything about partial adoption of the components of the package.

The qualitative study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, two experienced interviewers conducted 45 open-ended semi-structured interviews with farmers in the upstream area of the Mekong Delta. The respondents included both male and female farmers, as well as farmers who had received training on 1M5R and those who had not. All interviews were recorded (after seeking consent), transcribed into Vietnamese and translated into English. The transcripts were the basis of detailed coding of data to inform the development of close-ended survey questions.

The interviewers collected high quality open-ended data using the following good practices on qualitative data collection and analysis, which provided important insights into designing survey questions:

- Understanding both the ‘semi’ and ‘structured’ elements of a semi-structured interview. The structured element required that in the allotted time of approximately 1 hour, the interviewers cover all five domains – seeds, pesticides, fertilizers, water use and post-harvest losses – to provide consistency in data across interviews. However, within each domain, the interviewers had a lot of flexibility to change the way a question was phrased, probe and go deeper, or open a new line of questioning if fresh insights emerged.

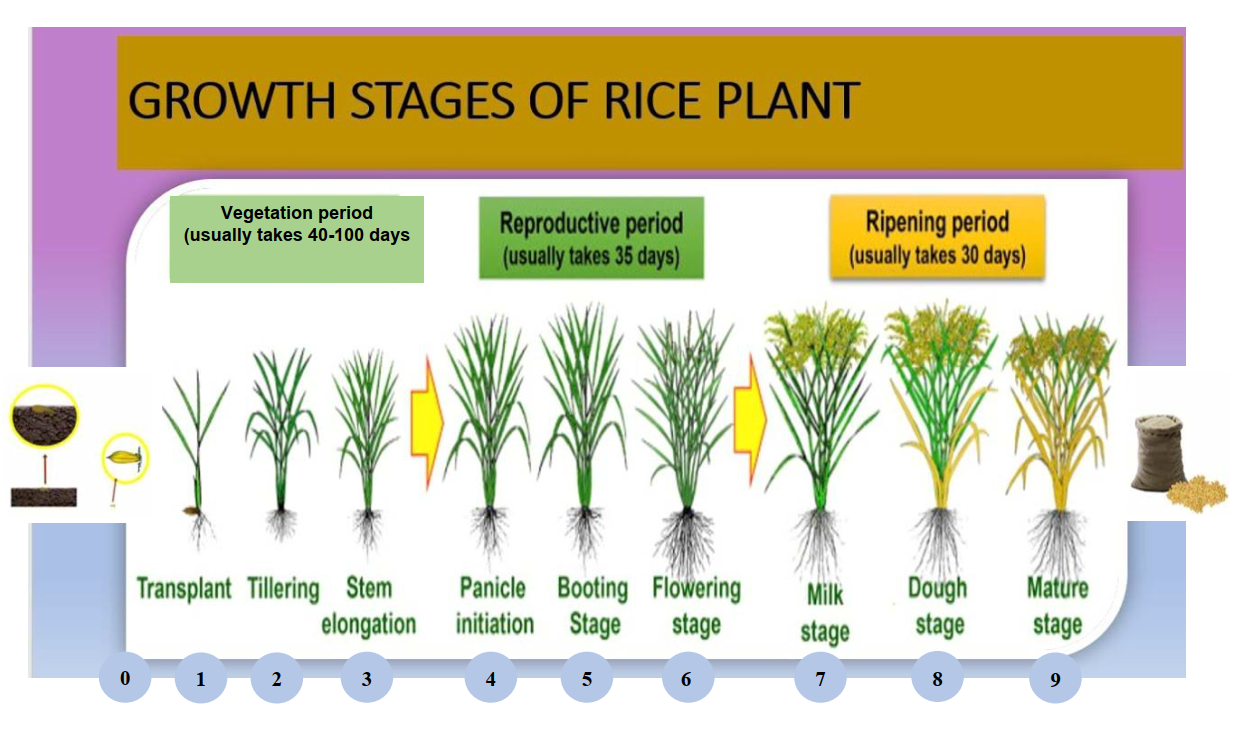

- Eliciting a concrete narrative based on actual, lived experience. Rather than make the respondents calculate, analyze, or use abstractions in response to questions, the interviewers conducted interactive conversations. For example, instead of asking “how many times in the last season did you apply pesticides?”, the interviewers asked the farmer to walk them through their pesticide applications in the last season from the time they sowed the seeds until they harvested the rice. By understanding the narratives of the farmers in their own words, we learned that farmers could easily recall each application and used the different growth stages in a cropping cycle as a reference point. The farmers talked about the pests against which they were spraying, whether they were mixing drugs during every spraying and whether the applications were for treatment or prevention. This gave us important clues about converting the qualitative data into close-ended survey questions and suggested that using a visual aid on the stages of rice growth would aid in recall. In addition, we learned what farmers could not reliably tell us without a lot of back-and-forth questions and explanations, which meant that we could not ask about these in a structured questionnaire: the names of drugs, the quantities used, or how long they had been following these practices.

Researcher Thao Thi Nhat Bach interviewing a farmer - Paying attention to the language and terminology used by farmers. As researchers, we were interested to get data on pesticides, which includes fungicides and insecticides, but excludes molluscicides, herbicides and rodenticides. But farmers often include all when asked about “pesticides”. It is only through probing and seeking clarifications that we understood two things: first, the term used for “pesticides” broadly translates from Vietnamese into English as “plant protection drugs” and second, some farmers might use the term broadly to include herbicides or molluscicides. It was important that the survey questions pre-empt any confusion on the part of the farmer. This resulted in two close-ended survey questions instead of one to ensure clarity. The first question asked, “how many times did you apply plant protection drugs on your main plot, including herbicides, molluscicides, insecticides, fungicides and rodenticides?” followed by “Of these, how many times did you apply insecticides and fungicides?”

- Coding and analysing qualitative data did not come from a predefined framework. Qualitative data analysis focuses on establishing the relationship between practices, including practices which may appear as outliers. For the coding, we created matrices on each domain to cover all agricultural practices under 1M5R. The codes were not derived from a pre-determined framework; instead, codes were developed inductively based on the actual practices of farmers and could be flexibly adjusted in the process of coding the data. The coding was the precursor to writing notes that aimed to connect the diverse practices using the logic of reality. After this period, the quantitative questions were formulated and further standardized. A stock of close-ended quantitative questions was then set up to be ready for Phase 2.

In Phase 2, we used the same technique of open-ended conversations, but rather than use a semi-structured interview guide, we used close-ended questions and conducted intensive field testing of the instrument across four sites. These sites were selected to cover the variation across all major rice-growing regions in Vietnam, namely Mekong River Delta, Red River Delta, North Central Coast and South-Central Coast. The goal was to understand which questions worked, but also probe deeply into which did not and why. This resulted in a further reworking of the survey questions. At the end of Phase 2, a draft survey module was handed over to a quantitative team to collect data on rice-farming in thirty sites across six provinces. The quantitative data was used to assess the relevance of proposed questions before integrating into VHLSS 2023. It is this kind of attention to detail on measurement issues that has helped SPIA to develop our partnership with the General Statistics Office of Vietnam. In the process we’ve learned more about how rice farmers describe their input use decisions than we ever thought we would.