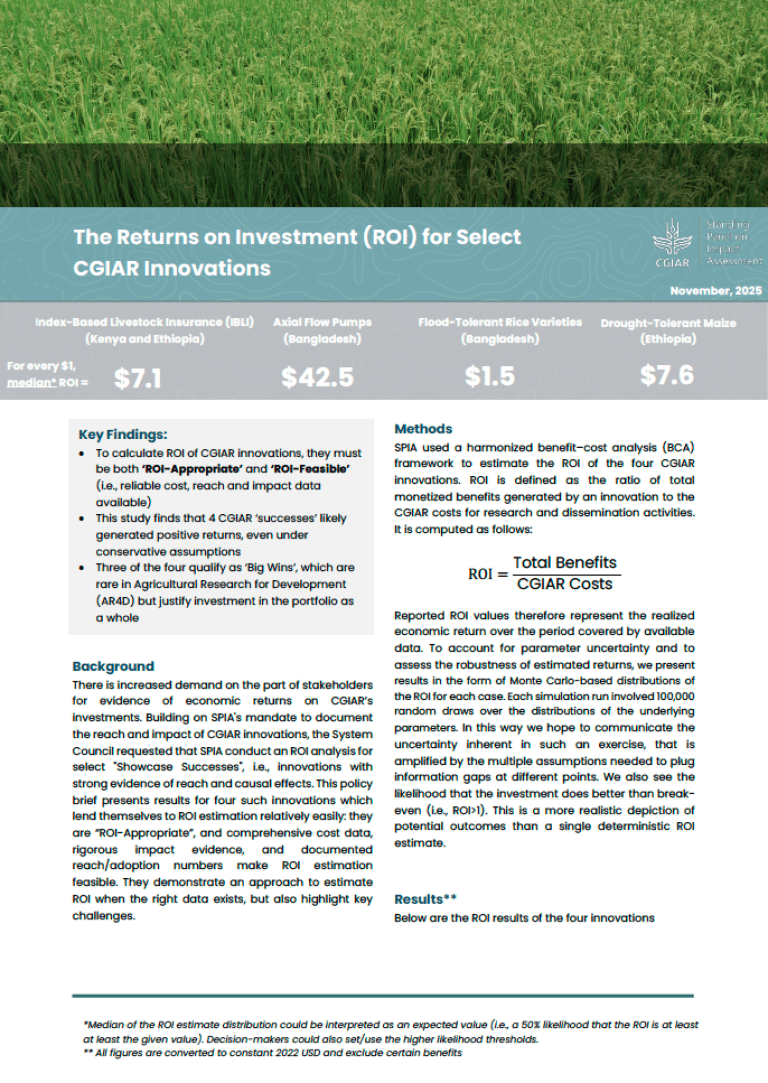

Here's a measurement dilemma: A drought-tolerant maize seed is created. Over four million Ethiopian farmers are found to adopt it, accounting for 63% of all maize growers in the country. That's remarkable reach. But does it automatically imply those farmers are better off? Usually, the answer is no. Meaning reach and impacts in people's lives are fundamentally different things. But occasionally, and under very specific conditions, high reach can reveal something meaningful about impact. The trick is knowing when.

Why Reach Normally Doesn't Equal Impact

It's tempting to believe that if millions of farmers freely choose to use improved maize seeds, those seeds must be helping them. After all, why would rational people adopt something that doesn't benefit them?

This logic works perfectly, in theory. It is a world where farmers have perfect information about how new seeds will perform, where they can easily afford to experiment, where they have insurance against crop failure, and where markets function smoothly.

Reality, however, is far more complex. Farmers make adoption decisions with incomplete information and credit constraints. They might adopt seeds because someone recommended them, because an NGO heavily subsidized them, or because they seemed promising during good weather, only to discover later that the seeds don't actually work better in their specific conditions.

Or the opposite: highly beneficial innovations might go unadopted because farmers can't afford them, don't trust unfamiliar technology, or lack secure land tenure that would make investments worthwhile.

When Adoption Tells Us Something About Impact

This doesn't mean reach data cannot be informative of impact. The key question is: under what conditions does a farmer's decision to adopt actually reflect that they're benefiting from the innovation?

The answer depends on how closely reality matches theory. When reach is measured at the household level, when land tenure issues can be circumvented, when adoption persists through climate and political shocks, when vulnerable individuals (particularly women) can influence uptake, and when farmers can learn from others or by doing, then high adoption becomes a more meaningful marker of impact.

Ethiopia's drought-tolerant maize is one of those rare cases that checks almost all these boxes. Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, adoption among maize-growing households jumped from 24 to 40%. Farmers made their own decisions to adopt, measured at the household level. Both learning from others, and learning by doing, were possible. The technology is portable and does not represent an investment in the land itself.

But what about persistence? Do farmers keep using the improved variety once they try it? This is where the dynamics of adoption become revealing. Between 2019 and 2021-22, only 6% of households switched from CGIAR to non-CGIAR varieties, while 20% switched to CGIAR varieties. Even more striking: the poorest 40% of households now adopt at similar rates to everyone else. Adoption rates almost doubled in three years despite civil conflict and drought. Few households switched away from improved varieties once they tried them.

That persistent growth through extreme conditions, combined with such limited dis-adoption, makes the case for inferring positive impact from high adoption rates stronger than usual. It's not causal evidence, but it's meaningful evidence, nonetheless.

Some Innovations May Be Trickier

Now compare the drought-tolerant maize example to that of two-wheeled tractors in Ethiopia. Only 4.3% of enumeration areas report the presence of two-wheeled tractors. Does low reach here mean low impact? Not necessarily. Take the case of Bangladesh, where just 3% of farmers own tractors, but almost every owner provides services to neighbors.

The Middle Ground

Understanding total benefits from agricultural innovations requires both reach and impact evidence. Reach data alone, even with evidence of millions of adopters, may not always tell us whether adopters are better off.

When only reach data exists, this technical note offers guidance on what might cautiously be inferred about impact. Acknowledging the wide gap between theoretical possibility and practical defensibility, and being transparent about it, is essential for credible claims about the apparent successes of CGIAR.