Women make up a larger share of agricultural employment in countries with lower economic development, where limited education, infrastructure, and off-farm job opportunities constrain options. In many sub-Saharan African countries, women represent over 50% of the agricultural labor force. Similarly, about half of the agricultural workforce is female in several Southeast Asian countries. Yet, women’s access to assets and resources such as land, inputs, training or finance lag behinds men’s, leading to significant gaps in productivity (The Status of Women in Agrifood Systems). Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa consistently shows that women-managed plots produce significantly lower yields than men’s—often due to unequal access to inputs, extension services, and productive resources, as well as structural barriers like discriminatory norms and market failures (Leveling the Field-Improving Opportunities for Women Farmers in Africa).

Integrating gender into agricultural development research is critical not only to acknowledge the role women play in agri-food systems, but also to better understand the extent to which women have access to extension services, technology adoption, productivity, and market integration. It also helps uncover the factors that influence these outcomes and assess the effectiveness of interventions, particularly among women farmers.

To properly integrate gender into agricultural development research, good data is crucial. Data should enable researchers to understand ownership, access, and decision-making at the individual level, rather than solely at the household level because the individuals within households do not always act as one. When designing survey modules, it is important to capture information on ownership, access, and decision-making related to key agricultural assets, inputs, and activities. For example, in sections concerning agricultural resource management, it is important to record information on land ownership, decisions regarding input use, crop selection, and how earnings from crop sales are managed. Modules on livestock ownership and management should identify individual animal ownership, and control over earnings from livestock sales or products. Sections on asset ownership will ideally identify not only if the household owns an asset, but specifically who within the household owns it and who makes decisions regarding that asset.

It is also important to capture individual access to extension services to identify who in the household received information on different topics, such as weather, markets, livestock rearing or crop production. On ownership, access, and decision-making within a questionnaire's agriculture modules, it is best to link these questions directly to the household roster. The approach involves identifying owners, decision-makers, or information recipients by listing up to two or three relevant household members from the roster, depending on the desired depth of information. This also allows to better link the agriculture outcomes with individual socio-demographic characteristics (For more information you can refer to the LSMS database).

Besides integrating gender into the core survey modules, incorporating sections specifically measuring women's economic empowerment is also important. Women's empowerment is both a means to improve agricultural productivity, health, or nutrition, as well as a development outcome in its own right, making its measurement essential in development studies. Collecting data on women’s economic empowerment allows for a deeper understanding of their access to resources, decision-making power, and participation in agricultural value chains. Including empowerment measures also helps capture women’s agency, reflecting their ability to make choices and act on them, while also showing how household dynamics influence their economic roles.

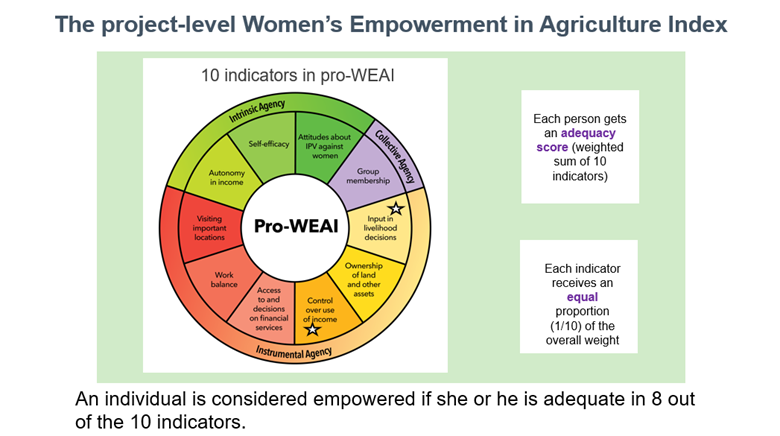

While there are many approaches for measuring empowerment, the suite of Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI)tools offers unique advantages. It uses information from both women and men in the same household, which enables users to measure intrahousehold empowerment gaps. It is now used by 280 organizations in 69 countries to monitor progress toward women’s empowerment and gender equality in different country contexts and different types of agricultural development projects. There are different versions of WEAI available for different types of users. The project level WEAI (pro-WEAI), in particular, was designed for measuring project impacts, but can also be used as a diagnostic to understand the empowerment profiles of women and men in project context and inform the design of interventions.

Pro-WEAI is made up of 10 equally-weighted indicators that measure three types of agency:

- intrinsic agency (power within),

- instrumental agency (power to), and

- collective agency (power with).

It uses the Alkire-Foster methodology for constructing the index and is fully decomposable by indicator and by subgroup.

One of the most common questions we receive about the WEAI is whether users can pick and choose which indicators to collect, or if all 10 indicators should always be collected in full. When using the pro-WEAI (or any WEAI) as a diagnostic, it's helpful to have a complete picture, because there may be unintended consequences that can be missed if only selected indicators are collected. For projects that have an explicit women’s empowerment goal, we highly recommend using the pro-WEAI quantitative survey and qualitative protocols.

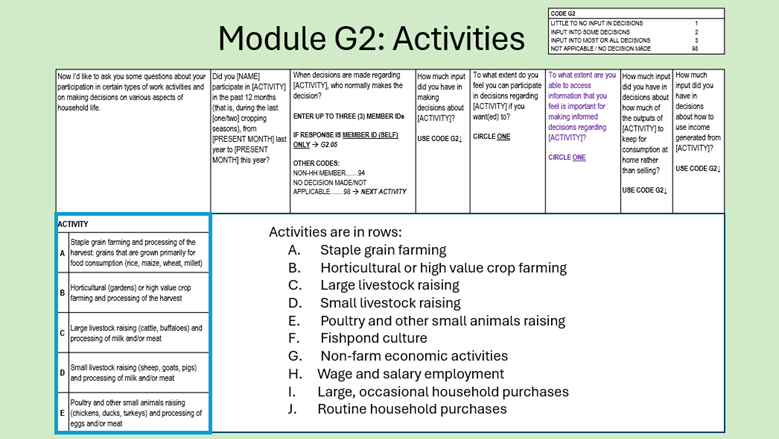

However, for projects where empowerment is not the primary outcome of interest, it can be difficult to justify especially when the survey is already long, and resources are limited. For this scenario, at the minimum, we recommend collecting the pro-WEAI module G2, which enables the calculation of two indicators: input in livelihood decisions and control over use of income.

These are some recommendations on how to integrate gender into survey design for agricultural development research, not only through specific modules to capture and measure women’s economic empowerment, but also by including questions for disaggregated information. This allows for a better capture of data on ownership, access, and decision-making, and overall intra-household dynamics.

Women play a key role in agri-food systems, yet their contributions are often overlooked, even in data collection efforts. To fully understand the dynamics of agri-food systems, the barriers farmers face, patterns to accessing technology, inputs, information and markets and drivers of productivity, it is key to properly include women in data collection efforts.

References

- Myers, Emily; Heckert, Jessica; Faas, Simone; Malapit, Hazel J.; Meinzen-Dick, Ruth S.; Raghunathan, Kalyani; and Quisumbing, Agnes R. 2023. Is women’s empowerment bearing fruit? Mapping women’s empowerment in agriculture index (WEAI) results using the gender and food systems framework. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2190. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136722.

- Quisumbing, A., Gerli, B., Faas, S., Heckert, J., Malapit, H., McCarron, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., Paz, F. (2023). Assessing multicountry programs through a “Reach, Benefit, Empower, Transform” lens, Global Food Security, 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2023.100685

- Quisumbing, AR.; Meinzen-Dick, RS.; Seymour, G; Heckert, J; Myers, E; GAAP2 for pro-WEAI Study Team; et al. 2024. Enhancing agency and empowerment in agricultural development projects: A synthesis of mixed methods impact evaluations from the Gender, Agriculture, and Assets Project, Phase 2 (GAAP2). Journal of Rural Studies 108(May 2024): 103295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103295

For more information about the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI), please contact IFPRI-WEAI@cgiar.org.